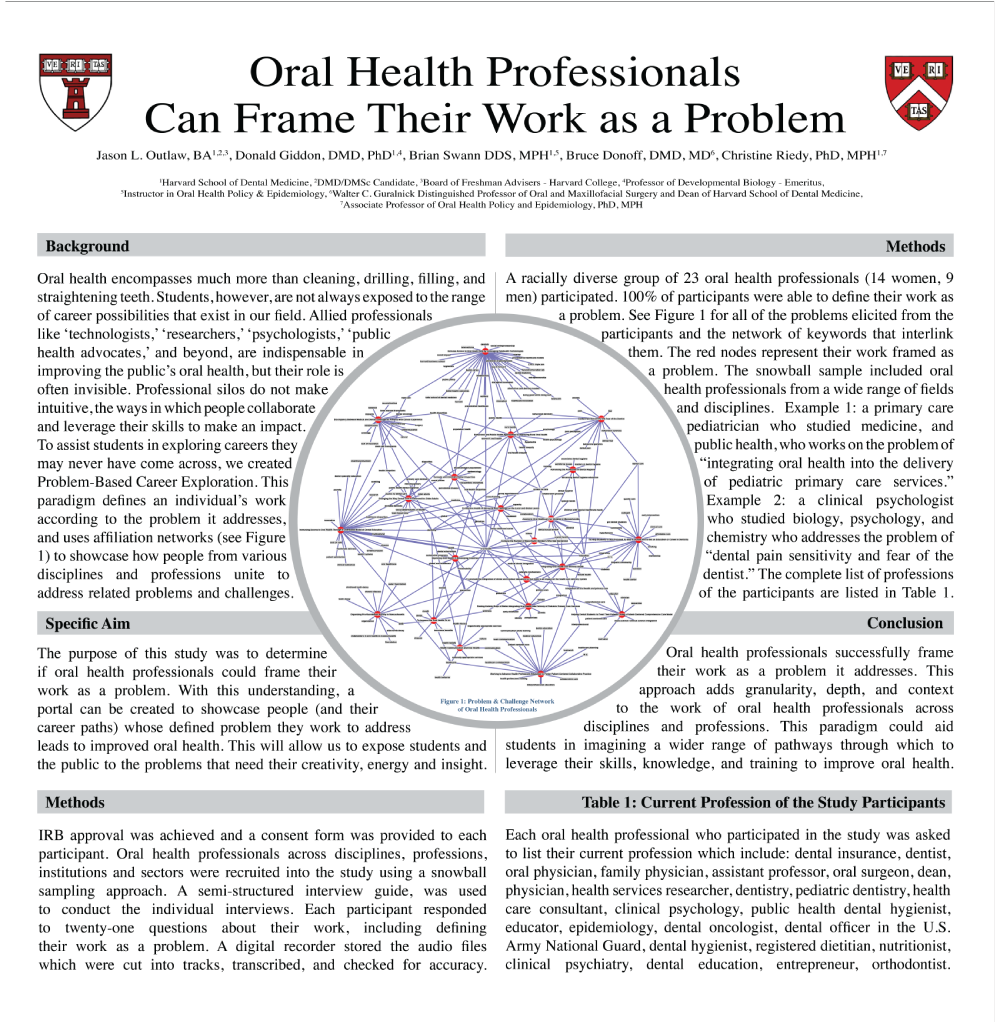

Purpose: Oral health encompasses much more than cleaning, drilling, filling, and straightening teeth. Students, however, are not always exposed to the range of career possibilities that exist in our field. Allied professionals like ‘technologists,’ ‘researchers,’ ‘psychologists,’ ‘public health advocates,’ and beyond, are indispensable in improving the public’s oral health but their professional labels do not intuit how they participate and leverage their skills to make an impact. To assist students in exploring careers they may never have come across, we created Problem-Based Career Exploration. This paradigm defines an individual’s work according to the problem it addresses, and uses affiliation networks to showcase how people from various disciplines and professions unite to address similar problems. The purpose of this study was to determine if oral health professionals could frame their work as a problem. With this understanding, a portal can be created to showcase people (and their career paths) whose defined problem they work to address leads to improved oral health. This will allow us to expose students and the public to the problems that need their creativity, energy and insight.

Methods: IRB approval was achieved and a consent form was provided to each participant. Oral health professionals across disciplines, professions, institutions and sectors were recruited into the study using a snowball sampling approach. A semi-structured interview guide, “The Professional Pathways Interview” was used to conduct the individual interviews. Each participant was asked to respond to twenty-one questions about their work, including defining their work according to a problem it addressed, the importance of that problem, the skills required to address it, the people with whom they collaborate, and the path that led them to where they are now. Each interview was recorded using a digital recording device. The mp3 files were cut into tracks, transcribed, and checked for accuracy.

Conclusion: A racially diverse group of 23 oral health professionals (13 women, 12 men) participated. All participants were able to define their work according to a problem it addressed. The following are example problem statements elicited from the interviews: Example 1 : a primary care pediatrician who studied medicine, and public health, who works on the problem of “integrating oral health into the delivery of pediatric primary care services.” Example 2 : a dental hygienist who studied elementary education and psychology who addresses the problem of “access to oral health care for children in Massachusetts.” Example 3 : a dentist who studied business, public health, and oncology who addresses the problem of “the discrepancy between medical and dental coverage for patients with cancer experience.” Example 4 : a clinical psychologist who studied biology, psychology, and chemistry who addresses the problem of “dental pain sensitivity and fear of the dentist.” Oral health professionals successfully frame their work as a problem it addresses. This approach adds granularity, depth, and context to the work of oral health professionals across disciplines and professions. This paradigm could aid students in imagining a wider range of pathways through which to leverage their skills, knowledge, and training to improve oral health.